You are here

April 10, 2015

Uneven provider rehabilitation adherence for Psychiatric Rehabilitation (PSR) has been a hot topic debated fiercely in legislation and provider associations across the country for several years (Williams & Green, 2012). Certainly, PRA has done their part to ensure that PSR practitioners across the country receive training and education on prescribed rehabilitation protocols and interventions. In addition, state Health and Welfare organizations, local schools and provider agencies have put on Continuing Education Seminars and offered them to providers in their communities.

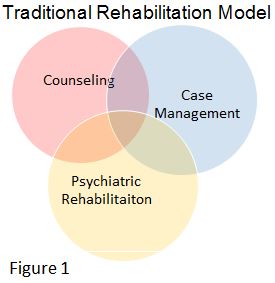

One reason for mixed rehabilitation adherence may be confusion over job duties and responsibilities. Many agencies which offer PSR services also offer Counseling and Case Management. These three services are often thought of as the community standard for mental health care (Bunger, 2010). However, practitioners and clients alike suffer from significant confusion on the roles and responsibilities of each of these services. Many see these as similar services which overlap each other in many ways, see figure 1.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) (Beck, 1976; DiGiuseppe, 2009) tells us that thoughts/feelings, behaviors and consequences work together in a cycle that can be positive or negative, see figure 2. When CBT is applied to the standard operating procedures of each agency offering counseling, case management and PSR, it can eliminate mixed rehabilitation adherence by creating more defined job roles. For example, counseling clearly addresses the inner feelings and thought processes that a client experiences (those that cannot be seen by an outside observer) (Goodstein, 1954). PSR, is focused on the observable behaviors that result from these thoughts and feelings. Case Management can then focus on addressing consequences. See figure 3.

Let’s use a case study to further illustrate how this works with PSR. Amy is a 10 year old girl referred to Child Protection services. When Amy was 8, her father left their home, having very intermittent visits and was often intoxicated. Amy became very anxious and was frequently upset due to her father’s infrequent visits.

From the time Amy was 8, until now, she has suffered mental, emotional and even some physical abuse at the hands of both her mother and her father. Amy's anxiety increased. She became afraid to go to sleep.

Amy states that she is afraid of dying in her sleep so she stays up during the night. Amy generalized her fear of dying to being sick and is now afraid of being sick. Amy has been going to the doctor regularly, missing a lot of school and her grades have fallen. Now, when she does go to school, she is so far behind that she feels overwhelmed and often sits in the bathroom and cries. She states that she feels anxious all the time.

Amy’s cognitive behavioral cycle likely consists of thoughts such as, “I’m scared all the time, I’m afraid I’m going to die,” etc. Her behaviors are clear; she has missed a significant amount of school, she is constantly going to the doctor, she is isolating herself, etc. As a consequence her grades are dropping and she sees the doctor frequently.

Amy is a good candidate for Counseling, PSR and Case Management. Amy’s PSR practitioner may focus on the observable behaviors that Amy is engaging in. Such interventions may consist of setting up bedtime and morning routines and practicing these routines with Amy until she is able to perform them independently. Amy and her PSR practitioner can also work on Self-Soothe Skills and practice using the skills in situations that provoke Amy’s anxiety (such as going to school or getting ready for bed). They can work on building positive emotions through positive experiences (mastering something, completing something, meeting a goal, facing a fear, etc.). By focusing on these goals, the PSR can prompt, support and encourage Amy in changing her observable behaviors. Additionally, Amy’s PSR worker can help her apply the skills that she is learning in counseling during in vivo exercises. The aim of Amy’s PSR worker should be to actively practice skills that will help her change and control her observable behaviors, as suggested by the cognitive behavioral model.

Amy’s story gives a great example of how collaborative efforts can help with the rehabilitation process. Psychiatric Rehabilitation is an integral part of the behavioral health framework and Amy’s recovery. I hope this scenario demonstrated how the collegial nature of these services support the success and recovery of even the youngest participants of psychiatric rehabilitation.

References

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press.

DiGiuseppe, R. (2009). An introduction to cognitive behavior therapies. In A. Akin-Little, S. G. Little, M. A. Bray, T. J. Kehle, A. Akin-Little, S. G. Little, ... T. J. Kehle (Eds.), Behavioral interventions in schools: Evidence-based positive strategies (pp. 95-110). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Goodstein, L. (1954). Review of 'The Dynamics of the Counseling Process'. Journal Of Educational Psychology, 45(4), 250-252. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association, USPRA (2015, January 1). Retrieved February 8, 2015 from www.uspra.org

Williams, N. J., & Green, P. (2012). Reliability and validity of a rehabilitation adherence measure for child psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35(5), 369-375. doi:10.1037/h0094495